Reticle Handler Team

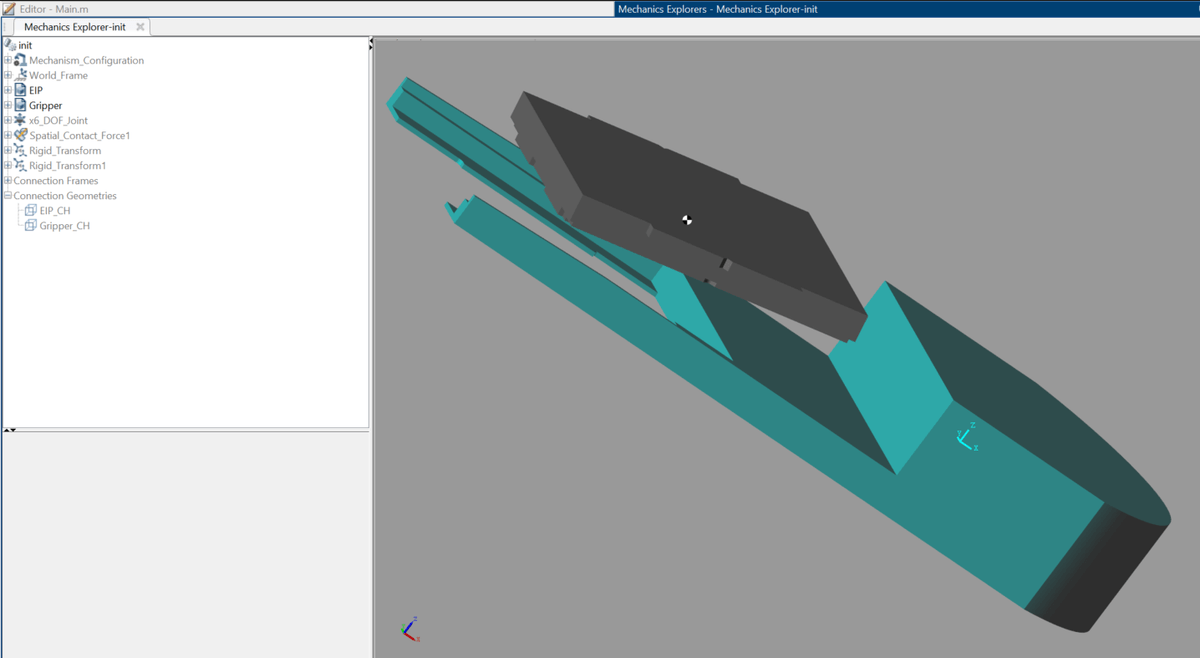

At ASML, I worked on the Reticle Handler team as a Robotics and Mechatronics Controls Engineering Intern. My main project was building a physics-accurate simulation in MATLAB Simscape to model the handoff dynamics of the OVR/IVR gripper system. This system is responsible for moving reticles (the photomasks used in EUV lithography) with extreme precision. Any misalignment during handoff can damage the reticle, contaminate the vacuum environment, or halt operations entirely.

The Problem

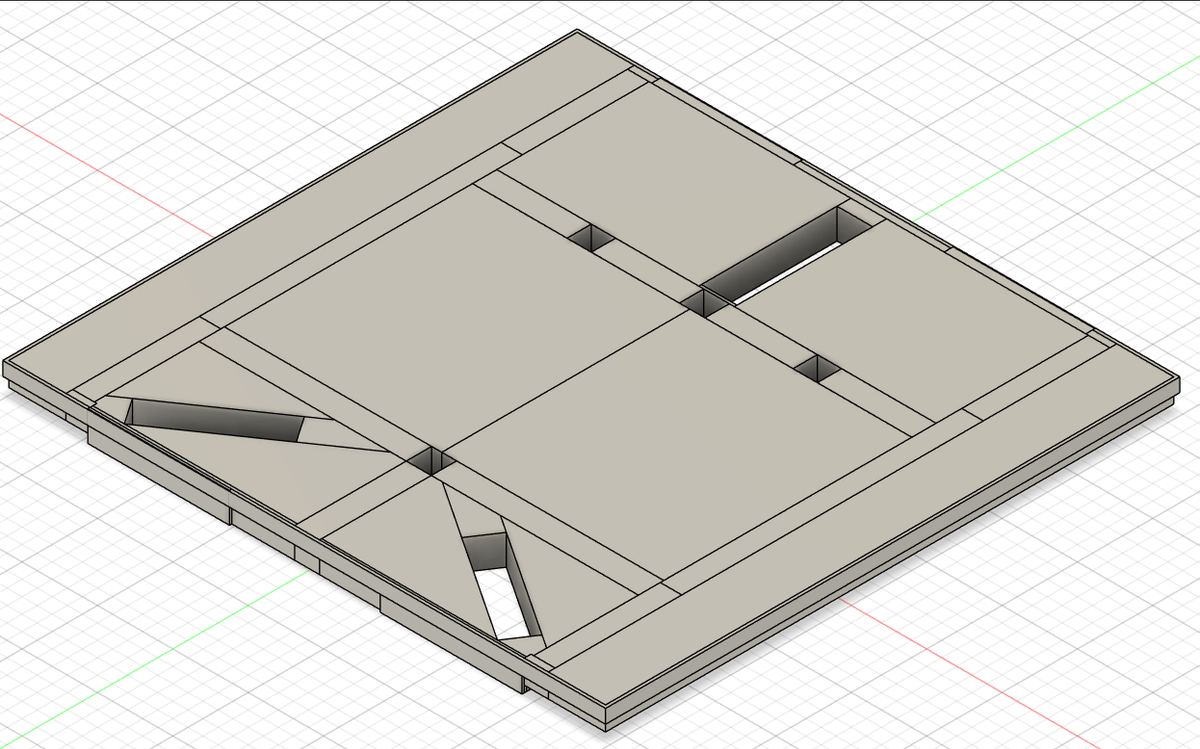

The OVR robot has to align and grip an EIP (a reticle carrier) with incredibly tight tolerances, then place it onto kinematic pins. The margin for error is basically nonexistent. To understand where failures could occur, I needed to build a simulation that could model slip dynamics, collisions, and vibrations across the entire gripper assembly.

The catch? MATLAB Simscape’s collision detection only works with convex meshes. The gripper and EIP components are complex, non-convex CAD assemblies with dozens of parts. I needed to find a way to decompose these geometries into convex hulls that Simscape could actually use.

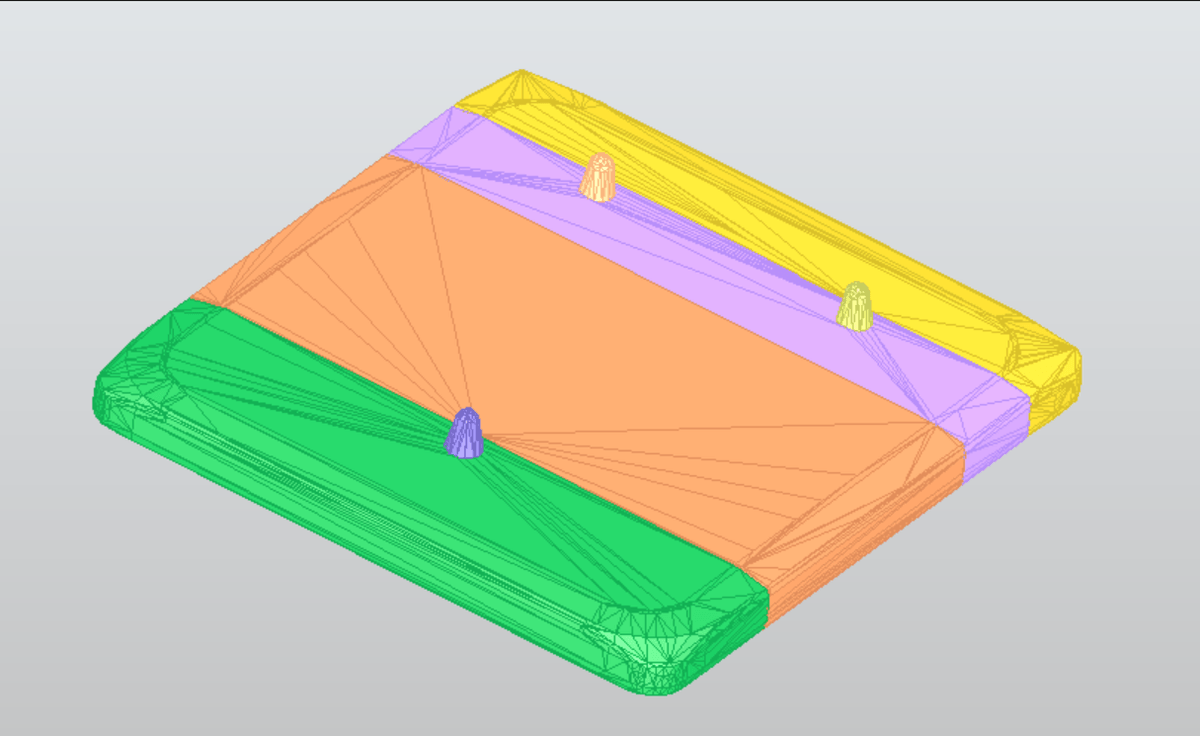

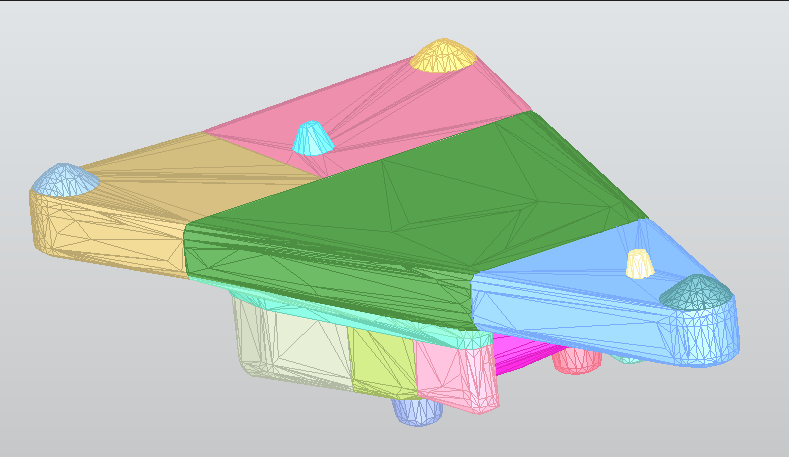

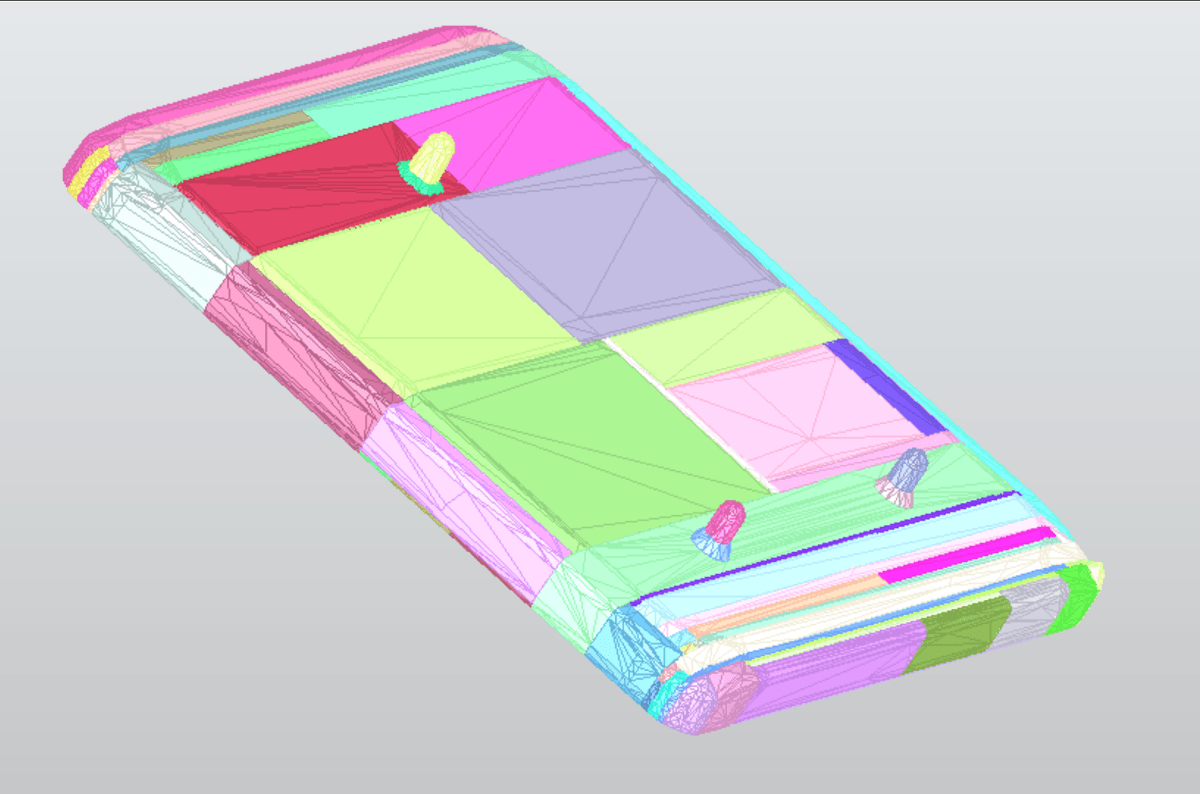

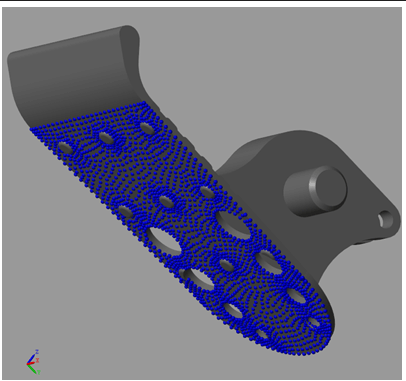

Convex Mesh Decomposition

This is where things got interesting. For collision detection to work in physics simulations, you need convex shapes. A convex shape is one where any line segment between two points inside the shape stays entirely inside the shape. Think of a sphere or a cube. But real mechanical parts have holes, cavities, and complex features that make them non-convex.

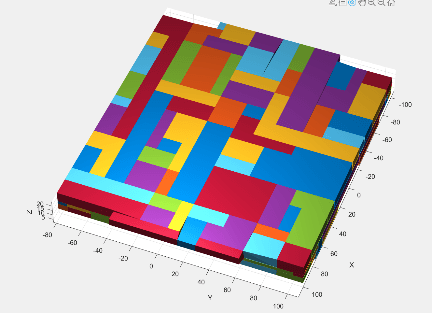

The solution is approximate convex decomposition, which breaks a complex mesh into multiple convex pieces. I evaluated several approaches:

Approximate Convex Decomposition with Collision-Aware Concavity (CoACD): This was the winner. Developed by Wei et al., CoACD uses a collision-aware metric to decompose meshes in a way that preserves the geometric features that actually matter for contact simulation. The implementation produces high-quality decompositions with minimal parts while maintaining accurate collision boundaries.

V-HACD (Voxelized Hierarchical Approximate Convex Decomposition): This method voxelizes the mesh first, then decomposes it. It’s faster but produces way more parts and loses fine geometric detail. For precision robotics simulation, this wasn’t good enough.

Manual CAD Decomposition: You can manually split parts in CAD software, but this doesn’t scale when you have dozens of components and need to iterate quickly.

Building the Pipeline

I built a pipeline that takes STEP files from our CAD system, processes them through CoACD via C++ and Python bindings, and outputs convex hulls that MATLAB Simscape can import directly. The workflow looked like:

- Export STEP files from the CAD assembly

- Convert to mesh format (STL/OBJ)

- Run CoACD decomposition with tuned parameters

- Import the convex parts into Simscape as collision geometries

The decomposition quality directly affects simulation accuracy. Too few parts and you miss collision points. Too many parts and the simulation becomes computationally expensive. CoACD’s collision-aware metric helped find the right balance automatically.

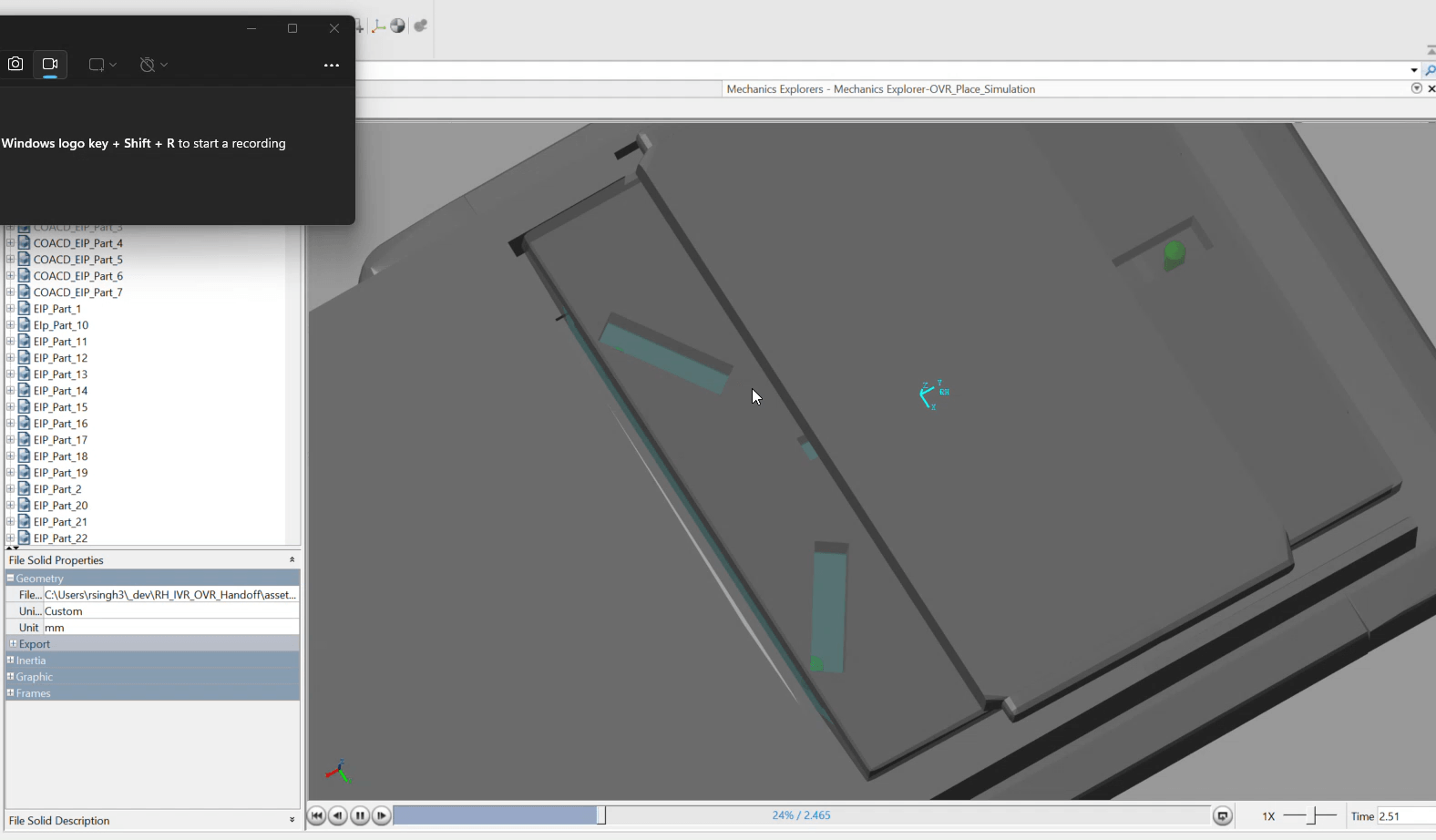

The Simulation

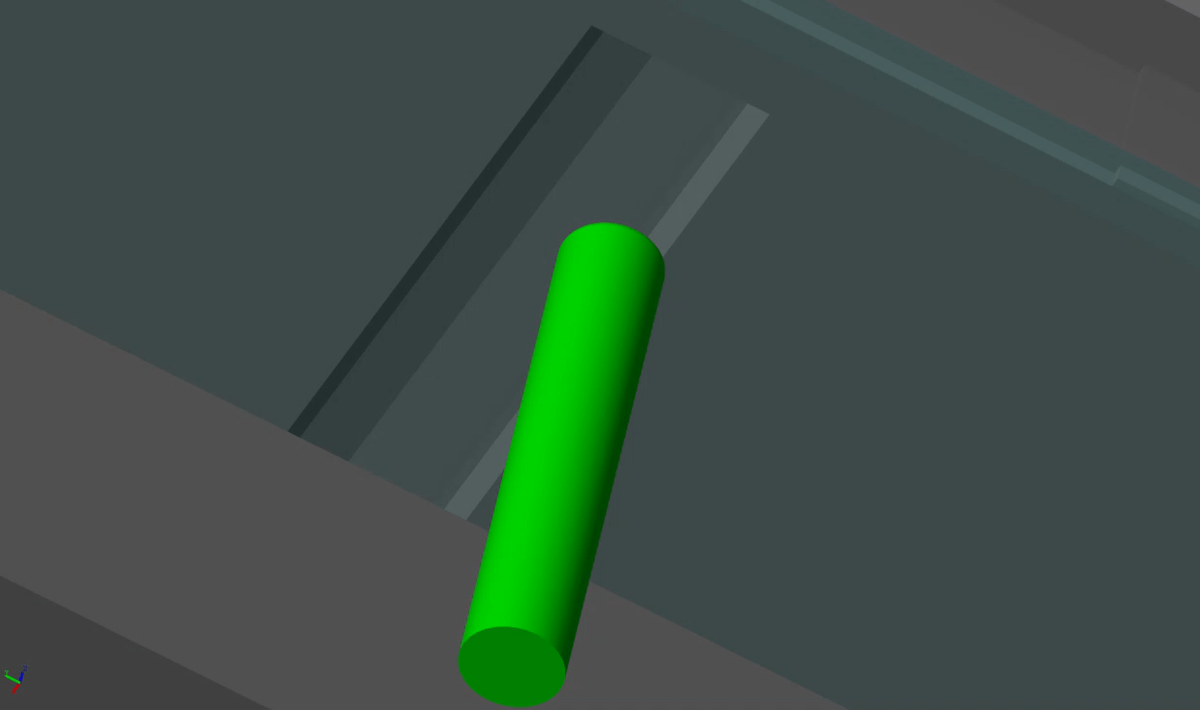

With the convex decomposition pipeline working, I built out the full Simscape model. The simulation includes the gripper arms, the EIP, the kinematic pins, and all the contact forces between them.

The kinematic pins are what lock the EIP in place after the gripper releases it. Getting this handoff right is critical.

Material Properties and Friction Research

Getting the geometry right was only half the battle. For the simulation to actually predict real-world behavior, I needed accurate material properties. This meant diving deep into tribology research and materials science literature to find the right values.

The gripper and EIP components are made from different materials depending on the part: aluminum alloys for structural components, hardened steel for the kinematic pins, and specialty ceramics and coatings in certain contact areas. Each material pair has different friction characteristics, and those characteristics change depending on whether you’re in atmosphere or vacuum, whether surfaces are lubricated, and even the surface finish from machining.

I spent a lot of time hunting down friction coefficients for specific material combinations. Some were straightforward (steel-on-aluminum is well documented), but others required digging through academic papers and manufacturer datasheets. For the vacuum environment specifically, friction behavior gets weird. Without air molecules to provide some boundary lubrication, metal-on-metal contacts can have significantly higher friction or even cold welding in extreme cases.

Beyond friction, I also had to characterize:

- Contact stiffness and damping - How “springy” the contact feels when parts collide. Too stiff and the simulation explodes numerically. Too soft and parts pass through each other.

- Coefficient of restitution - How bouncy collisions are. For precision handoffs you want very little bounce.

- Material densities - For accurate inertia calculations. The simulation needs to know how heavy each part is and how that mass is distributed.

The trickiest part was that some of these values aren’t published anywhere. ASML uses proprietary coatings and surface treatments, so I had to work with the materials team to get estimates or run sensitivity analyses to understand how much uncertainty in these parameters affected the simulation results.

Running 100,000+ Simulations

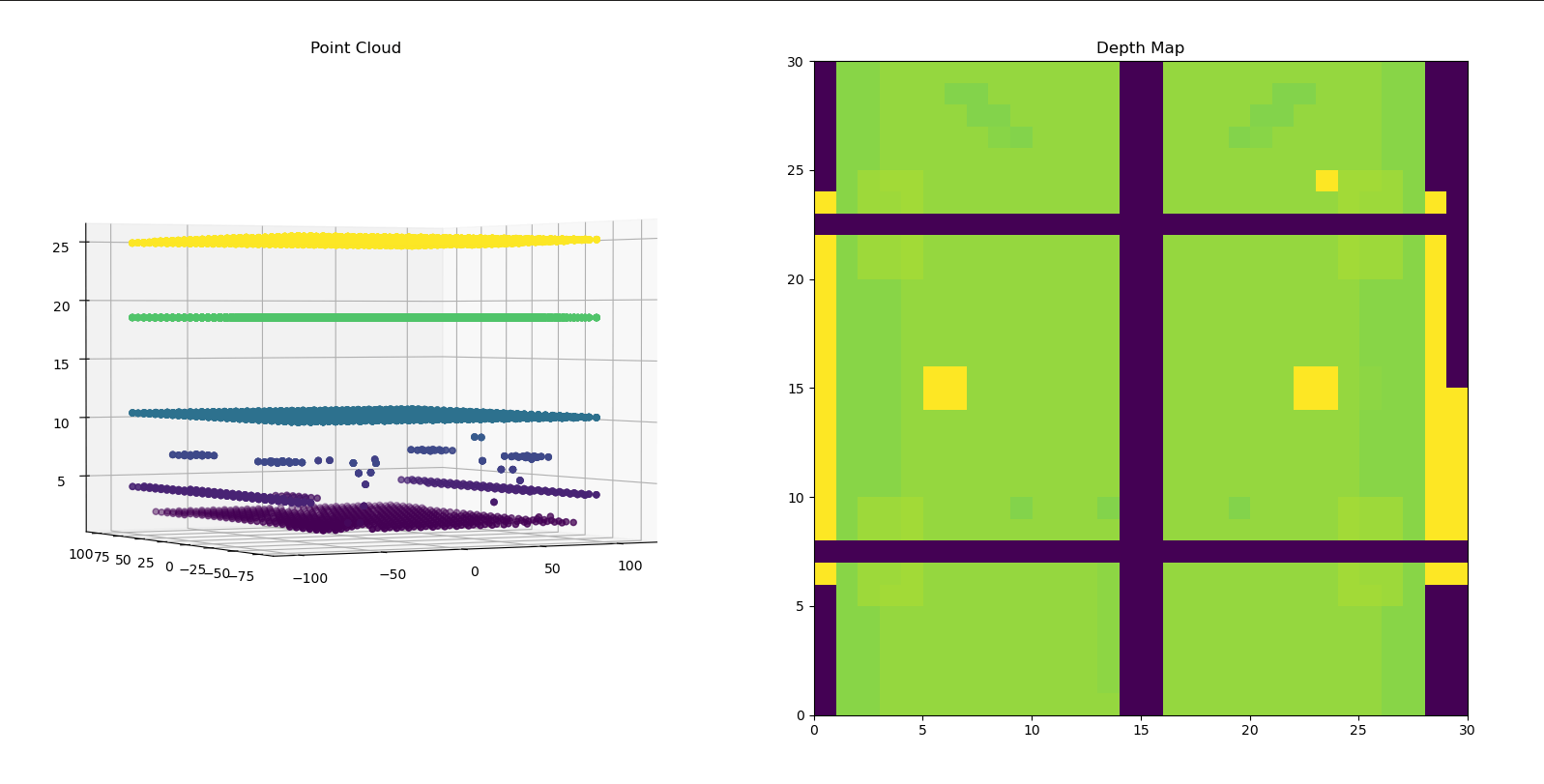

The real value of the simulation came from running massive parameter sweeps. I ran over 100,000 different combinations varying:

- Gripper positions and orientations

- Initial misalignments

- Calibration errors

- Contact friction coefficients

- Approach velocities

This helped identify the tolerance thresholds where handoff would succeed vs fail. We could see exactly which misalignment conditions caused collisions, which caused the reticle to slip, and which caused vibrations that exceeded acceptable limits.

Other Approaches I Explored

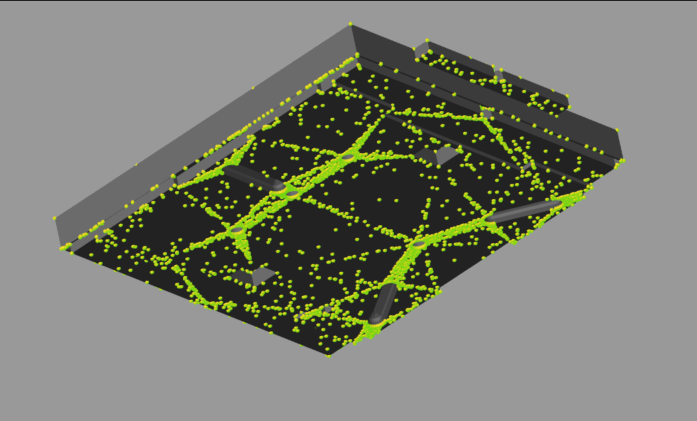

I also experimented with point cloud estimation for surface contact modeling. The idea was to represent surfaces as dense point clouds and compute contact forces based on point penetration depth.

This approach has some advantages for deformable surfaces, but for rigid body contact between precision-machined parts, the convex decomposition method worked better.

Results

The simulation validated our proof of concept. The kinematic pins successfully engage with the EIP and achieve realistic locking behavior in simulation. More importantly, we now have a tool to:

- Test sensor placement configurations and their impact on detection accuracy

- Introduce calibration errors and evaluate system robustness

- Vary gripper positions to identify exactly where the tolerance boundaries are

This kind of simulation-driven analysis would have been impossible to do with physical prototypes alone. Running 100,000 physical tests isn’t practical, but running 100,000 simulations overnight is.

Looking Back

This internship pushed me to combine a bunch of different skills: computational geometry, physics simulation, software engineering, and robotics. The convex decomposition problem in particular was a fun deep dive into a niche area of computer graphics that turned out to be critical for making the simulation work. Getting to apply cutting-edge research (the CoACD paper came out in 2022) to a real industrial problem was exactly the kind of challenge I was hoping for.